Yellowstone Notebook

Was there ever a Yellowstone on Mars? - Caldera Chronicles

Was there ever a Yellowstone on Mars?

By Yellowstone Volcano Observatory November 24, 2025

Yellowstone is not just a fantastic natural laboratory for Earth-based studies. A better understanding of hydrothermal activity in the first National Park can also provide clues about what Mars might have looked like long ago.

Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. This week's contribution is from R. Greg Vaughan, research scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey, and Steve Ruff, associate research professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University.

Today, Mars is a cold and dry planet with a very thin, low-pressure atmosphere. It has water, but it's all frozen, locked up in underground ice (like permafrost) and in polar ice caps. But billions of years ago Mars had a thicker atmosphere and a warmer and wetter climate. It also used to have active volcanoes. So, with all that heat, and all that water, is it possible that there were once hot springs on Mars? And how could we find out?

Mars has been a fascination for centuries, with early telescopic observations and fantastically speculative (and as it turns out, fictional) stories about possible canals and intelligent life forms. Modern Mars exploration began in the 1960s with spacecraft flybys, then in the following decades with orbiters, landers, and finally robotic rovers. There are currently seven active spacecraft orbiting Mars and two robotic “geologists” roving the surface, named Curiosity and Perseverance.

With all the images and data collected by these satellites and robotic explorers, we now have a good idea of what Mars is like on the surface. There is no evidence for canals or complex lifeforms, but there is plenty of evidence for active surface processes, like wind, dust devils, migrating sand dunes, and landslides. There is also evidence for past volcanism, such as large volcanoes and lava flows, and evidence for past flowing liquid water, such as river channels and delta deposits. The evidence for past liquid water also includes a variety of hydrated minerals, hydrothermal alteration minerals, and silica deposits. It’s the silica deposits, discovered in 2007 by the Mars Exploration Rover, Spirit, that make you sit up and say, “Wow! Like in Yellowstone?”

Most of the silica deposits in Yellowstone are made of a white, lightweight, porous rock composed of opaline silica. The silica is dissolved from the rhyolitic volcanic rocks below and picked up by the hydrothermal fluids circulating underground. When the hot, silica-rich fluids reach the surface, they cool down and precipitate layered silica deposits and mounds, called sinter, around geysers and hot springs. There is also another way to get silica-rich deposits: acid-sulfate leaching. This is where sulfuric acid from volcanic gases reacts with the surrounding silicate rocks near the surface, leaching (removing) metal compounds, like iron and magnesium, and leaving a residue of opaline silica.

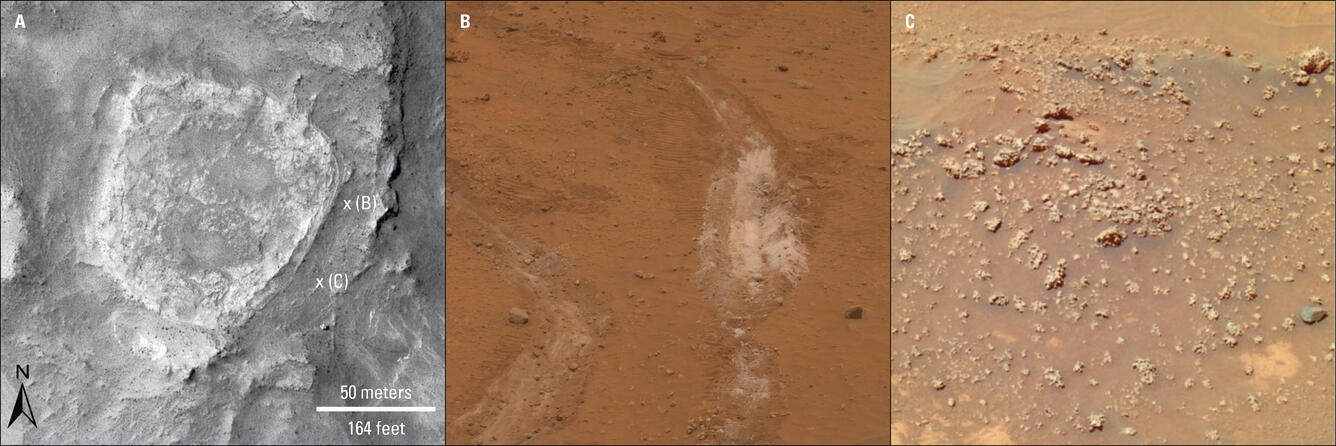

On Mars, silica deposits were found adjacent to a site dubbed Home Plate, within a large impact crater called Gusev crater, and there is evidence they formed from hydrothermal fluids. A key observation is the association of the silica deposits with volcanic activity. The Home Plate feature represents the remains of volcanic ash deposits, which, along with nearby basaltic rocks, demonstrates that this place had magmatic activity capable of generating a hydrothermal system, although much smaller than the one that drives Yellowstone’s hot springs and fumaroles.

Because sinter deposits on Earth often host microbial life, they are a key target in the search for evidence of ancient microbial life on Mars. Excitingly, the silica deposits discovered by Spirit display tiny fingerlike structures that resemble features of Yellowstone sinter and other sinter deposits on Earth that are referred to as stromatolites, which form by a combination of biology and geology. The colorful microbial communities that inhabit the edges and outflow channels of hot springs contribute to the growth of stromatolites along with the silica that precipitates from the water. The fingerlike structures observed by Spirit are made of silica, but they have not been shown to include organic matter and may not be equivalent to hot spring stromatolites on Earth. At this point, they are assumed to have formed from geologic processes alone.

Still, understanding microorganisms that inhabit Yellowstone’s hot springs, and the evidence they leave behind, could help answer some fundamental questions in the field of astrobiology: is there, or has there ever been, life elsewhere in the solar system?

Going beyond Mars, there is also evidence of geyser activity on some of the icy moons in the outer solar system, such as Neptune’s moon, Triton, and Saturn’s moon, Enceladus. Jupiter’s moon, Europa is another outer solar system body that has a liquid water ocean underneath its crust of water ice and may host geysers that are spurting out samples of this water. In October 2024, NASA launched the Europa Clipper mission to investigate. It will arrive in 2030. Stay tuned.

Yellowstone is not just a natural laboratory for Earth science studies. With its history of caldera-forming volcanism, geothermal activity, geysers, hydrothermal mineral deposits, and thermophilic bacteria, it is also an excellent laboratory for exciting planetary science research.

For more about hot spring deposits on Mars, see the following publication: Ruff, S.W., Campbell, K.A., Van Kranendonk, M.J., Rice, M.S. and Farmer, J.D., 2020. The case for ancient hot springs in Gusev crater, Mars. Astrobiology, 20(4), p.475–499, https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2019.2044.